Explained below...

One of the first statistics that someone who is researching religion in Japan will come across is that when statistics are collected the total membership of the main religions when added together equates to almost double the population of Japan. So for instance, in 2006 the Japanese Agency for Cultural Affairs reported that there were 106.8 million Shinto adherents and 91.2 million Buddhists while the total population of Japan was 127.8 million people.

The explanation for these strange statistics is very straightforward- in Japan most people do not regard religions as exclusive and this includes the various temple and shrine authorities who collect the statistics. This attitude is illustrated quite nicely by the fact that it is common in Japan for a person to have Shinto ceremonies shortly after they are born and at certain ages (3, 5 and 7) throughout their childhood, have a Christian wedding when they get married and have a Buddhist funeral after they die. It is also relatively common for individuals to be unaware of what Buddhist sect they and their family belong to until after a close relative dies and they need to contact a temple and summon the relevant priests.

The mixing of different religions traditions together is called syncreticism and the extent to which syncreticism plays a role in Japan has lead some researchers of religion in Japan to envision a kind of universal ‘Japanese religion’ in which all the different religions in Japan play interlinking roles, hence the common phrase ‘Born Shinto, Die Buddhist’.

Such a laissez faire attitude to religious segregation has caused much consternation to missionaries throughout history who arrived on Japan’s shores hoping to spread a message of their being only one ‘true’ religion.

A good example of the kind of difficulties faced and the syncretic nature of the Japanese religious environment is illustrated by the so called ‘hidden Christian’ communities (Kakure Kirishitan). The ‘hidden Christians’ were converts to Christianity who mantained their traditions and practices up until the modern period despite a two hundred year ban on Christianity in Japan . They managed to survive throughout this period of persecution by practicing their religion underground; hiding Christian icons in Buddhist and Shinto statues, passing prayers down through secret oral traditions and mantaining a secret and overlapping hierarchy.

These ‘hidden Christians’ still today regard themselvesas Christian and yet the syncretic effects that the Japanese religious enviroment has had on their beliefs is undeniable. For instance, one influential text describes God (called Deus) as having 200 ranks, 42 special marks and reigning over the twelve heavens which is a description which would be much more fitting in a Buddhist sutra than in a Christian text. Doctrinal rewrites were also not out of the question as in the hidden Christians doctrines God being a good God eventually forgave Adam and Eve and let them come back into heaven and similarly Jesus was allowed to sacrifice himself on the cross not in order to redeem everyone elses sins but so that he could repay the debt he owed the 44,444 children who had died when Herod ordered all the first borns in Egypt killed to try and get Jesus.

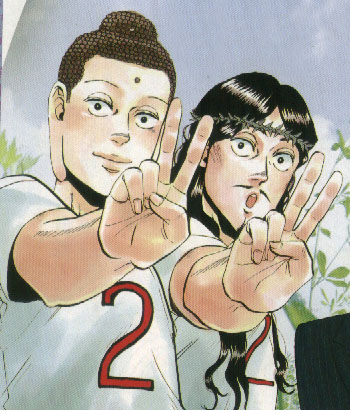

The hidden Christians are a slightly esoteric example but I was reminded of them by a billboard I noticed when visiting a manga store in Tokyo recently. The billboard was for a manga called ‘Saint Young Men’ (Saint-Oniisan) which features a story revolving around Jesus and Buddha taking a holiday from heaven and living together in an apartment in Japan. And if you want to take a look for yourself the series has been translated and posted online here.

Jesus & Buddha visit a Tokyo book store.

Now it’s true that this publication is a bit quirky even by Japanese pop culture standards but my point is I doubt that such a publication would a) likely make it to the shelves in the UK or America or b) become popular enough with the public to have large displays in chain book stores. The concept is certainly still quirky to a Japanese audience, but the juxtaposition of two iconic religious figures from different traditions is really nothing out of the ordinary.

Which leads me to the final example I’d like to offer in support of my point: the Toyokawa Inari Shrine/Temple in Tokyo. This is another site I visited in Tokyo but what distinguishes it from most other Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples in Japan is that it is both a Shrine and a Temple located on the same grounds. This set up used to be very common across Japan however during the ‘modernisation’ of Japan in the Meiji period there was a policy of enforced separation between Buddhism and Shinto. This was largely due to the government’s promotion of a new nationalist ideology which included Shinto being presented as the single official religion of the state.

Many shrines and temples resisted this enforced separation but the policy inevitably had effects and it is now quite rare to find combined temples and shrines today especially in cities like Tokyo where the main efforts of the government were concentrated.

The Myogonji Temple in Tokyo is an exception to this rule and it certainly offers a potent visual symbol of just how far the religious systems of Japan can become intertwined. The temple is Buddhist and yet the imagery that suffices the site is of the Shinto deity Inari and indeed Inari is recognised to be the main focus of worship at the temple. There is also a Shinto shrine located on the temple premises identified clearly by the distinctive red Torii gate that marks its entrance.

Inari is portrayed in a variety of different forms but popular examples include a young female goddess, an old man carrying rice and a fox. Foxes are also recognised as servants of Inari and as such fox statues are a staple of Inari shrines and Myogonji is no exception, as you can see below.

Inari foxes at Myogonji Buddhist Temple

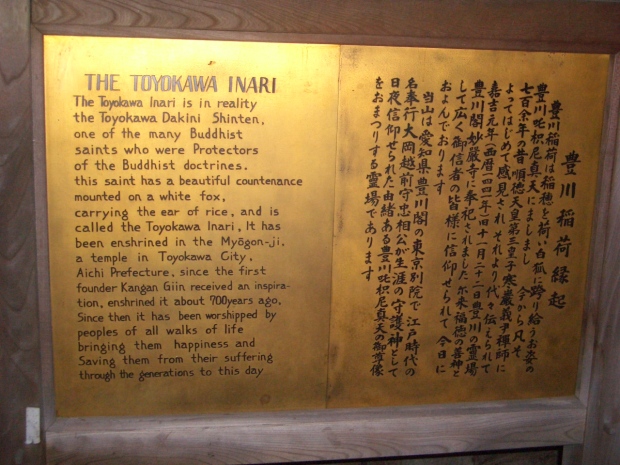

Inari is one of the foremost Shinto deities (known as kami) to the extent that over a third of the Shinto shrines in Japan are dedicated to him/her so the immediate question this raises is how this Buddhist temple manages to justify its preoccupation. The answer is that 1) as described above shrines being on temple grounds used to be the common setup and 2) Inari was identified as being a female Buddhist deity (Dakini Shinten) who rode on a fox. This second explanation for the apparent incongruity also happens to be set out quite clearly by the temple itself in a notice located at the entrance to the temple grounds.

Temple Sign at Myogonji in Tokyo.

This temple, the Jesus and Buddha manga and Hidden Christians are just examples of the undeniable atmosphere of syncreticism that infuses religion in Japan. However, it would be wrong to assume that this means that religious authorities and/or governments and individuals have never advocated religious exclusivity in Japan. The Meiji decree officially separating Buddhism and Shinto is one example but there are many others and there have been several periods in Japan’s history when religious groups have been persecuted or faced an outright ban as with Christianity in the seventeenth century.

It’s worth baring this in mind before thinking that Japan is a land of pure religious tolerance but regardless of the more complex picture the glaring fact remains that when it comes to religion, in Japan, the more notable feature is the inclusivity as opposed to the exclusivity we typically encounter in Western societies.

3 comments